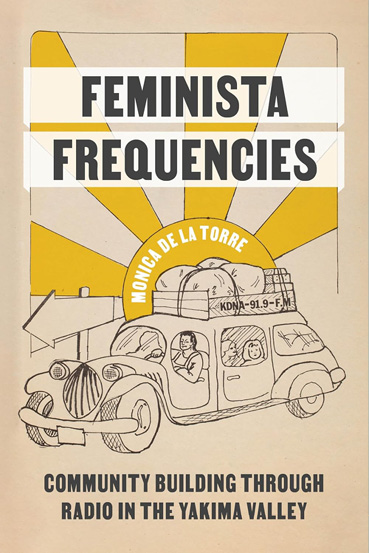

Feminista Frequencies: Community Building through Radio in the Yakima Valley

In Feminista Frequencies, Monica De La Torre offers a historical account of Chicana/o activism in the Pacific Northwest via the emergence of Radio Cadena (KDNA), a community radio station created by and for Chicana/o and Mexicana/o farmworkers in Washington’s Yakima Valley. As the title implies, she is particularly interested in the active roles Chicanas played in the creation and operation of the station through what she calls “Chicana radio praxis” (11), a feminist approach to radio that emphasizes community building, programming content not heard on other stations, and “keeping records,” or, in other words, archival practices. This approach to radio production, she contends, results in the transmission of “feminista frequencies,” which she uses to refer to actual soundwaves but also “as a metaphor for social movement activism. Here, radio frequencies carry discourses of resistance and track migrant movement across the United States . . . and across borders” (12). De La Torre argues further that, beyond simply documenting the history of Radio Cadena, Feminista Frequencies itself “mobilizes Chicana radio praxis as a methodology by building relationships with former Chicana and Chicano radio producers, identifying sound in nonauditory artifacts, and creating new archives” (11).

In Feminista Frequencies, Monica De La Torre offers a historical account of Chicana/o activism in the Pacific Northwest via the emergence of Radio Cadena (KDNA), a community radio station created by and for Chicana/o and Mexicana/o farmworkers in Washington’s Yakima Valley. As the title implies, she is particularly interested in the active roles Chicanas played in the creation and operation of the station through what she calls “Chicana radio praxis” (11), a feminist approach to radio that emphasizes community building, programming content not heard on other stations, and “keeping records,” or, in other words, archival practices. This approach to radio production, she contends, results in the transmission of “feminista frequencies,” which she uses to refer to actual soundwaves but also “as a metaphor for social movement activism. Here, radio frequencies carry discourses of resistance and track migrant movement across the United States . . . and across borders” (12). De La Torre argues further that, beyond simply documenting the history of Radio Cadena, Feminista Frequencies itself “mobilizes Chicana radio praxis as a methodology by building relationships with former Chicana and Chicano radio producers, identifying sound in nonauditory artifacts, and creating new archives” (11).

The book is divided into three chapters, the first of which, “The Roots of Radio Cadena: Chicana/o Community Radio Formations in the Pacific Northwest,” considers the foundational years of the station within the historical context of passage of the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 and the adoption and use of public broadcasting by the Chicana/o Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Within this context, De La Torre argues that the early years of the station demonstrate a convergence of “migration, social movement activism, and community radio production,” as the migrant farmworker and activist backgrounds of the station’s founders and broadcasters influenced their work in community radio, particularly their emphasis on efforts to build community (26). Regular readers of NEXO may recognize in this chapter the names of two of Radio Cadena’s co-founders, Julio César Guerrero and Dan Roble (Daniel Robleski), organizers who traveled to Washington to replicate the farmworker-produced radio initiative they first implemented in Lansing, Michigan.

The second chapter, “Brotando del Silencio (Emerging from Silence): Chicana Radio Praxis in Community Public Broadcasting,” documents the lives and work of women at Radio Cadena to examine how Chicana feminist thought and practice informed the operation of the station and the programming that appeared on its airwaves. De La Torre argues that the work of women at KDNA “altered the cultural soundscape of public broadcasting by creating Chicana-focused radio programs designed to reach farmworker women” that “extended beyond entertainment and into the realm of care” (62). They achieved this through a Chicana radio praxis that included: women in leadership positions and on air; training other women in radio production; producing programs especially for the women in their communities; and insisting on antisexist policies, including banning songs with sexist lyrics from their broadcasts.

In the final chapter, “Radio Rasquache: DIY Community Radio Programming Aesthetics,” De La Torre draws connections between the Chicana radio praxis of the women of Radio Cadena and more recent Chicana and Latina community radio and podcast producers. While contemporary producers may not know the stories of previous generations of producers such as those at KDNA, De La Torre argues that “the conditions and structures that call us to produce are similar” and entail similar tactics: “bring information, alternative epistemologies, and entertainment to people who are not included in mainstream media” (27). Here she employs an autoethnographic analysis to her own work with the Los Angeles-based community radio program, Soul Rebel Radio, to suggest linkages between the “rasquache” aesthetics of Radio Cadena and contemporary Chicana/o community-based media.

In Feminista Frequencies, De La Torre provides a meaningful and engaging addition to a small but growing body of literature on Chicana/os and Latina/os in the Pacific Northwest, long a destination for Mexicana/o and Tejana/o farmworkers. A notable feature of the book is De La Torre’s commitment to community-engaged research, as she highlights throughout the book her working relationship with former station manager Rosa Ramón. Theirs is a relationship demonstrably based in mutual respect and reciprocity that did not end with publication of the book. As De La Torre writes in the epilogue, “Ramón and I continue our collaboration in public talks and conference presentations about our work to digitize and archive Chicana radio” (112).

The book will appeal most obviously to scholars of Chicana/o and Latina/o social movements, especially to those with interests in feminism and gender or in the use of media by social movements. It will also appeal to general readers with similar interests, and her development of concepts such as “feminista frequencies” and “Chicana radio praxis,” while nuanced and innovative, are written in such a way that a general readership would still find the book accessible. At only 176 pages (inclusive of front matter, end notes, bibliography, and index), the book could be used in graduate seminars and upper-level undergraduate courses in Chicana/o and Latina/o studies or media and cultural studies. Students in these disciplines may find the book especially useful for De La Torre’s clear elucidation and modeling of Chicana radio praxis.