Unpacking 21st Century Immigration Policy

Introduction

For many Americans, mention of immigration policy under the Trump administration will forever call to mind images of children huddled in chain-link cages, some sleeping on mats on the floor, covered in foil blankets. Photographs taken inside a U.S. Border Patrol facility in McAllen, TX—published on June 17, 2018, and followed on June 18 by an audio recording of detained immigrant children crying out for their parents—shocked the nation and drew broad and swift criticism of the administration’s “Zero Tolerance” policy that resulted in the separation of children, including infants, from their parents. Addressing reporters outside the facility on June 17, Representative Filemon Vela, a Democrat from Texas, stated that previous presidents “decided there was one place they would never go and that was to separate families. This administration … has made that decision.” Former First Lady Laura Bush, whose husband oversaw the indefinite detention and torture of detainees at Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib detention centers, called Trump’s policy “cruel” and “immoral” in a June 17 Washington Post op-ed.

Following public outcry, Trump on June 20 issued an executive order directing the Department of Homeland Security to halt family separations except where parents may pose a risk to children. Contrary to Representative Vela’s statement that Trump had crossed a line previous presidents were unwilling to cross, Trump claimed to Telemundo anchor José Díaz-Balart that, “When I became president, President Obama had a separation policy. I didn’t have it. He had it. I brought the families together. I’m the one that put them together.” Factcheckers quickly disproved Trump’s claim, noting that family separation was a direct consequence of his administration’s Zero Tolerance policy, and that family separations were not a matter of policy during the Obama administration. But Vela’s claim is also misleading, as family separations did sometimes occur under the administrations of both Barack Obama and George W. Bush even though it was the policy of both administrations to keep families together in most cases.

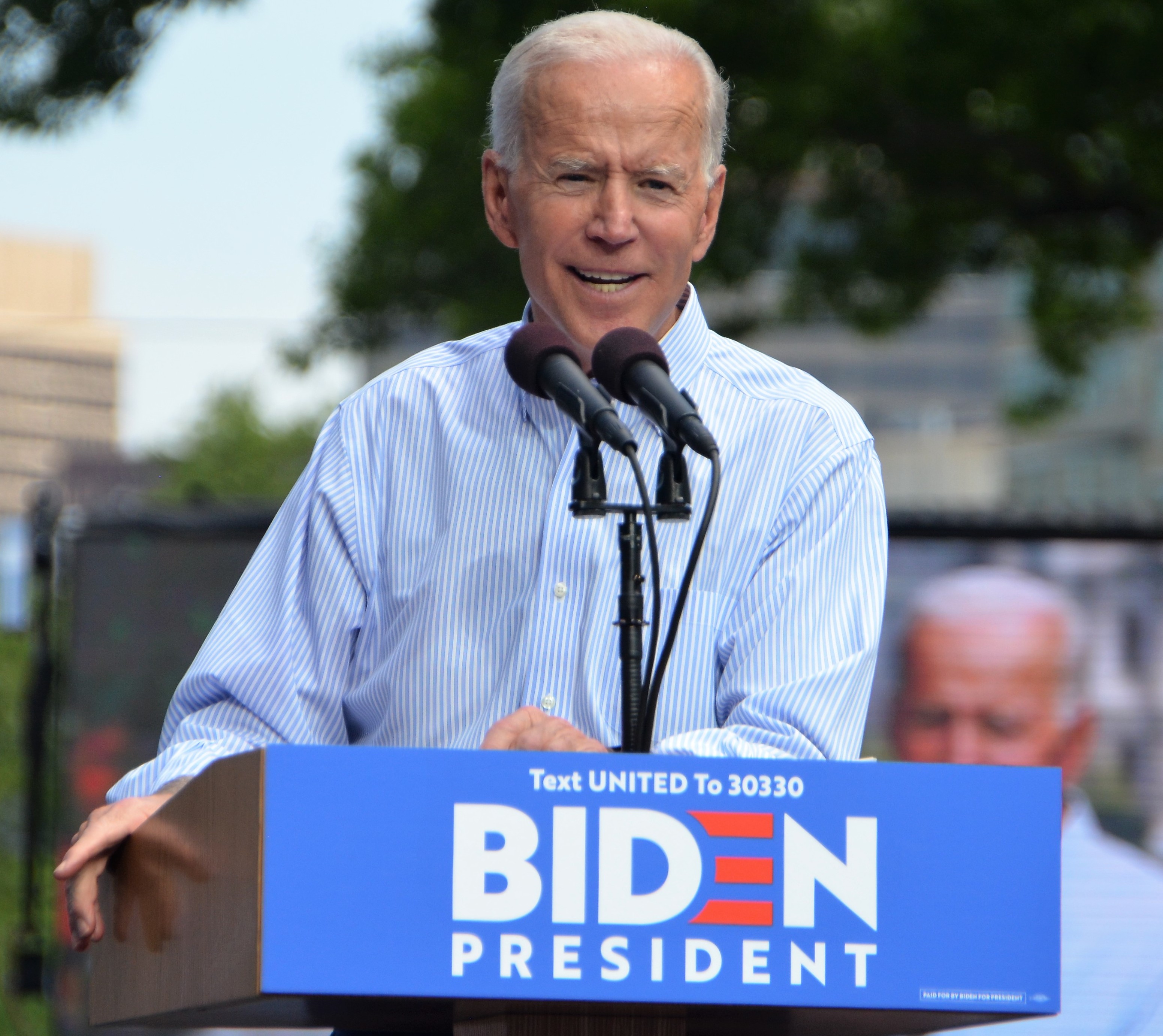

This clarification is a useful starting point in considering how the Biden administration should approach ongoing immigration crises. Public discourse often frames Biden’s immigration policy agenda as an effort to roll back the cruelty of Trump-era immigration enforcement initiatives. Framing the issue in this way, however, obscures the inhumane treatment of migrant detainees under previous administrations, treatment which the Trump administration amplified and openly embraced as official policy. Understanding Trump-era immigration policy in the context of shifts in policy in the broader post-9/11 era illuminates the failings of the Bush and Obama administrations that precipitated and enabled the actions of the Trump administration. This in turn allows for a more robust discussion of how the Biden administration can work toward approaches to immigration that recognize the role of the United States in creating these crises, as well as the dignity and humanity of those arriving in search of safety and economic security.

The current crisis began during the Bush administration with the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and restructuring of immigration enforcement. The creation of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the movement of Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) from the Department of Justice (DOJ) to DHS signaled a shift in priorities in the post-9/11 era from immigration enforcement as primarily an issue of criminal justice to one, first and foremost, of national security. The Obama administration then ratcheted up several Bush-era enforcement strategies, such as the Consequence Delivery System (CDS) and the Secure Communities program, which led to a significant increase in the number of removals of noncitizens compared to Obama’s predecessors. Even as the total number of deportations declined across each year of his presidency, his administration’s use of formal removals as opposed to voluntary returns earned Obama the nickname “Deporter-in-Chief.” The Trump administration then used the language of national security to justify extreme actions on immigration, including a ban on travel from seven Muslim-majority countries and the use of family separation as a strategy of deterrence. Finally, while Biden’s statements on immigration as a presidential candidate suggested a break with the priorities of past presidents, the Biden administration’s actions on immigration to date largely leave in place the policies of his predecessors rather than instituting alternative approaches that value the human dignity of immigrants to the United States.

The Bush Administration

When George W. Bush assumed the office of the President in 2001, he and his administration inherited from the Clinton administration new immigration laws passed in 1996. In an effort to appear tough on criminals and supposed abusers of government programs, Clinton signed into law in 1994 the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which introduced the “three strikes” rule for violent felonies and allowed states to enact mandatory minimum sentences. In 1996, he signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act, which imposed new restrictions on access to social welfare programs. Along similar lines, that same year, Clinton also signed into law two bills that made immigrants in the United States—regardless of legal status—vulnerable to deportation. The Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA), passed in the wake of the 1995 domestic terror attack in Oklahoma City, OK, gave immigration enforcement agencies expanded powers of detention and deportation and authorized fast-track deportation procedures. The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) likewise expanded powers of detention and deportation, as well as placed new restrictions on asylum seekers and enabled cooperation between federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies.

The impacts of AEDPA and IIRIRA were swift, with an increase of almost 61% in the number of yearly removals of immigrants from the U.S. in 1997, the year in which the laws went into effect. Muzaffar Chishti, Sarah Pierce, and Jessica Bolter (2017), writing for the Migration Policy Institute, define a “removal” as “the compulsory movement of a noncitizen out of the United States based on a formal order of removal,” whereas a “return” is “the movement of a noncitizen out of the United States based on permission to withdraw their application for admission at the border or an order of voluntary departure.” “Deportation,” they state, is “a general, nontechnical term describing the movement of a noncitizen out of the United States through either a formal removal or a return” (para. 6). The number of formal removals, which increased by an additional 65% from 1997 to 1998 and continued to increase steadily for the remainder of Clinton’s presidency, demonstrate the punitive nature of the 1996 laws, as removals carry greater legal consequences than returns, including prohibitions on reentry into the U.S. Though the number of removals increased immediately following implementation of the laws, Chishti, Pierce, and Bolter (2017) contend that “many of these enforcement tools were not deployed and fully resourced until the Bush administration, mostly in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks” (para. 7).

The 9/11 attacks spurred a major shift in the Federal Government’s framing of immigration enforcement from one of criminal justice to one of national security, along with a dramatic restructuring of immigration enforcement agencies. The Homeland Security Act, signed into law in November 2002, created a new Cabinet department, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which became operational in 2003. Reflective of the new framing of immigration enforcement as national security, immigration enforcement responsibilities were transferred to DHS. The United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), an agency created in 1933 and housed within the Department of Labor until 1940 when it was transferred to the Department of Justice, was dissolved by the Homeland Security Act. Three new DHS agencies were created to handle immigration and border security matters: United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), which processes and adjudicates visa, naturalization, and asylum and refugee matters; United States Customs and Border Patrol (CBP), which enforces customs and immigration regulations at U.S. borders; and United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which enforces customs and immigration regulations in the interior U.S. as well as conducts counter terrorism investigations.

These agencies grew significantly in size from their creation in 2003 until 2008 and employed more draconian tactics in their operations. CBP grew from 10,000 agents in 2003 to 17,000 in 2008, while ICE increased in size from 2,700 agents to 5,000 during the same time period (Chishti, Pierce, and Bolter, 2017). Ramping up the shift in tactics following the passage of AEDPA and IIRIRA, CBP in 2005 implemented the Consequence Delivery System to deter repeated attempts at entry by immigrants previously deported. Chishti, Pierce, and Bolter (2017) state, “instead of allowing unauthorized entrants to return to Mexico voluntarily, without any meaningful legal consequences, formal removal proceedings became far more common as did criminal charges for illegal entry or re-entry” (para. 10). The Bush administration also promoted interagency information sharing on immigration, criminal, and national security issues through interoperable data systems that were accessible to Cabinet agencies, as well as increasingly to local law enforcement. In March 2008, the administration also introduced the Secure Communities program, which allowed local law enforcement to match fingerprints against Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and DHS databases.

Counterintuitively, shifts in immigration enforcement priorities and tactics under Bush did not lead to an increase in the total number of deportations under his administration compared to his predecessor. From 1993 to 2000, the Clinton administration oversaw a total of 12,290,905 deportations, compared to 10,328,850 total deportations during the Bush administration of 2001-2008. Though overall deportations fell by approximately two million under the Bush administration, formal removals more than doubled during Bush’s presidency, from 869,646 under Clinton to 2,012,539 under Bush, while voluntary returns fell from a total of 11,421,259 under Clinton to 8,316,311 under Bush. Thus, formal removals accounted for almost 20% of all deportations during the Bush administration compared to just 7% during Clinton’s administration. Chishti, Pierce, and Bolter (2017) note that removals peaked in 2008 at 359,795, with approximately 240,000—or 67%—of those coming from the interior U.S.

The Obama Administration

Immigration enforcement under the Obama administration saw both continuations of and departures from Bush-era tactics and priorities. In terms of continuing Bush-era tactics, by 2011 CBP was employing the Consequence Delivery System along the entire length of the U.S.-Mexico border, while the Secure Communities program was operational in all U.S. jails and prisons by 2013. Federal funding for immigration enforcement skyrocketed following the creation of DHS, jumping from $6.2 billion in 2002 to $12.5 billion in 2006, and continued to grow during the Obama administration. By 2012, federal funding for immigration enforcement had grown to almost $18 billion, “a figure 24 percent higher than funding allocated to all other principal federal criminal law enforcement agencies combined (the FBI, Drug Enforcement Administration, Secret Service, U.S. Marshals Service, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives)” (Chishti, Pierce, and Bolter, 2017, para. 13).

Obama also inherited from his predecessor the Secure Fence Act of 2006, which authorized construction of 700 miles of fencing along the U.S.-Mexico border. The bill also authorized increased use of technological surveillance of the border, including cameras, satellites, and drones. At the time of signing, Bush said of the bill, “This bill will help protect the American people. This bill will make our borders more secure. It is an important step toward immigration reform.” Obama, then a Senator for the State of Illinois, voted in favor the bill—as did then-Senator Biden—but promised during his presidential campaign the next year to review the bill should he win the election. Yet, in April 2009, by which time 613 miles of new fence had been built, the Obama administration allowed new construction to begin in both Texas and California. By May 2011, 649 miles had been built and construction was completed in 2015.

Obama’s campaign promise to review border fence construction focused primarily on the environmental impact of construction. Another consequence of border fencing, though, was to compel migrants to find new routes through more dangerous territory, in particular the Sonoran Desert. A Government Research Service report from 2009 points to the human cost of fence construction in a section titled, “Unintended Consequences.” The authors state, “one unintended consequence of this enforcement posture and the shift in migration patterns has been an increase in the number of migrant deaths each year; on average 200 migrants died each year in the early 1990s, compared with 472 migrant deaths in 2005” (Haddal, Kim, Garcia, 2009, p. 33). Though illegal border crossings dropped in the first years of the Obama administration, CBP data show that migrant deaths reached 477 in 2012. By 2013, as Stuart Anderson notes in a policy brief from the National Foundation for American Policy, this meant that unauthorized immigrants were 8 times more likely to die while attempting to cross into the U.S. than in 2003.

The year 2012, however, also marked a point of divergence between the immigration enforcement priorities of the Obama administration and those of the Bush administration. From 2012 until the end of his presidency, Obama prioritized the removal of migrants recently apprehended while crossing the border, as well as those convicted of serious crimes, rather than those who violated the terms of their immigration status. He also issued the executive order, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which enabled some undocumented migrants brought into the U.S. as children to defer deportation orders for at least two years. Following this shift in priorities, the number of removals at the border shot up in 2012 while removals from the interior U.S. began a sharp decline. At the start of Obama’s first term, border removals accounted for approximately 53% of all removals, compared to 47% for interior removals, whereas by the end of his second term, interior removals accounted for only 19% of all removals compared to 81% for border removals. Of those removed from the interior U.S. in 2016, more than 90% had been convicted of serious crimes.

Still, the Obama administration’s use of formal removals over voluntary returns followed a trend started by the Clinton administration in the wake of AEDPA and IIRIRA and continued under the Bush administration. In fact, Obama’s use of formal removals far outstripped that of his predecessors even as the total number of deportations during his presidency was slightly more than half of the total number during the Bush administration. While total deportations fell from 10,328,850 under Bush to 5,281,115 under Obama, formal removals under Obama increased by around 50% from those by his predecessor, from 2,012,539 during the Bush administration to 3,094,208 under Obama. Likewise, while the Bush administration oversaw about four times as many voluntary returns as formal removals (2,012,539 removals compared to 8,316,311 returns), under the Obama administration, removals surpassed returns by nearly 1 million (3,094,208 removals compared to 2,186,907 returns). Given the longer-lasting legal consequences of formal removals compared to voluntary returns, criticism of Obama’s record from immigrant rights advocates comes into focus.

The Obama administration’s response in 2014 to the arrival of tens of thousands of asylum seekers from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, which relied upon detention and expedited removal of “recent arrivals,” laid the groundwork for the Trump administration’s response to similar crises. Since many of these migrants arrived in family groups, DHS under the Obama administration made it a practice to detain families for the duration of their removal proceedings with the aim of deterring future migrant families. On paper, it was the policy of the administration to keep families together while in detention but, as Leigh Barrick writes for the American Immigration Council, “the truth is that a mother and child who are sent to family detention will often have been separated by DHS from other loved ones with whom they fled—including husbands, fathers, grandparents, older children, and siblings” (2016, p. 1). Barrick argues that ICE’s practice of sending mothers and children to facilities separate from the rest of a family unit causes psychological trauma and makes it difficult for family members to collectively pursue asylum. A September 2016 report of the DHS Advisory Committee on Family Residential Centers similarly concluded that separating mothers and children from other family members was never in the best interest of the children and advised against the practice as a strategy of deterrence. The report further argued against the general use of family detention for the same reason. Despite these concerns, family detention and separation would soon return in more extreme versions under the Trump administration.

The Trump Administration

Despite criticism from the Left over his administration’s record-high use of formal removals, Obama was still attacked from the Right for being soft on immigration. This supposed softness provided an opening for Donald Trump to launch his presidential campaign by attacking Mexican immigrants—as well as Central and South Americans and migrants from the Middle East—as violent criminals and a threat to national security. Trump began his announcement address by declaring, “our country is in serious trouble,” before claiming, “the U.S. has become a dumping ground for everybody else’s problems. … When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. … They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with [them]. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists” (Trump, 2015). To combat the supposed lack of border security under Obama, Trump later in the speech promised to secure the U.S.-Mexico border through construction of a border wall, stating, “I would build a great wall, and nobody builds walls better than me, believe me, and I’ll build them very inexpensively, I will build a great, great wall on our southern border. And I will have Mexico pay for that wall” (Trump, 2015). Trump’s openly inflammatory and xenophobic pronouncements were a clear indication of the hard line his administration would take on immigration. Many of the most controversial actions of his administration, however, relied upon the same mechanisms used by or put in place by his predecessors.

On the campaign trail, Trump routinely criticized Obama’s use of executive orders as an overreach of executive power. Though executive orders are common and often uncontroversial, they are also at times used to bypass Congress on controversial issues. Both Bush and Obama used executive orders in this manner, Bush to create the detention camp at Guantánamo Bay and Obama to create DACA, along with a further executive order issued in 2014—Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA)—that would have offered similar protection to parents of children with U.S. citizenship or permanent residency but was blocked in court. Contrary to his prior criticism of Obama’s usurpation of power through executive orders—a precedent set for Obama by Bush—just days into his administration, on January 30, 2017, Trump issued the first in a series of contentious executive orders on immigration.

Executive Order 13767, titled “Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements,” contained numerous directives and declarations including, for example, that CBP hire 5,000 additional Border Patrol agents, and that “State and local law enforcement agencies across the country [be empowered] to perform the functions of an immigration officer in the interior of the United States to the maximum extent permitted by law” (p. 1). The order also directed the Secretary of Homeland Security to “take all appropriate steps to immediately plan, design, and construct a physical wall along the southern border” (p. 2), and, already backtracking on his promise that Mexico would pay for the wall, to identify available federal funds and to prepare Congressional budget requests. In December 2018, not having received Congressional funding for the wall, Trump provoked the longest government shutdown in U.S. history by saying he would veto any spending bill that did not include funding for the wall. Shortly after Trump relented and signed a spending bill, he attempted to bypass Congress by issuing Proclamation 9488 titled “National Emergency Concerning the Southern Border of the United States.” Even as the legality of the emergency declaration was being challenged in court, money was diverted from other federal agencies to fund the wall, mostly from the Department of Defense. By the end of the Trump administration, these dubiously procured funds paid for construction of 455 miles of barriers along the border, nearly all of which replaced existing barriers; only 49 miles of new barriers were constructed.

Two days after his executive order on border security, Trump issued two more orders on immigration. One, officially named “Protecting the Nation from Terrorist Attacks by Foreign Nationals” and commonly referred to as Trump’s “Muslim Ban,” barred citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the U.S. for 90 days, as well as indefinitely suspending admission of refugees from Syria and all other refugees for 120 days. The other, “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States,” reprioritized immigration enforcement to target for removal immigrants convicted of or charged with criminal offenses, and even those who “have committed acts that constitute a chargeable criminal offense” (p. 2), a dramatic reversal of Obama’s prioritization of those convicted of serious crimes. The order further threatened to disqualify sanctuary cities from Federal grants, called for weekly publication of a list of crimes committed by undocumented immigrants, and created the Office of Victims of Immigration Crime Engagement. These latter provisions highlight the Trump administration’s narrative that undocumented immigrants pose a threat to public safety, despite evidence that immigrants commit crimes at lower rates than the native-born.

The Trump administration also worked diligently to limit the number of migrants admitted to the U.S. on humanitarian grounds. In the first year of his presidency, Trump lowered the annual ceiling for refugee admissions from 85,000 when he entered office to 50,000, to 45,000 in 2018, 30,000 in 2019, and finally to a record low of 18,000 in his final year in office—with only 11,814 refugees actually admitted in 2020. Comparatively, when Bush entered office, the ceiling was 90,000, which he then dropped to 80,000, then to 70,000 in 2002 where it stayed until 2008, when it was raised back to 80,000. Obama left the ceiling at 80,000 until 2012 when it was dropped to 76,000, then down again to 70,000 from 2013 to 2015, after which it was raised to 85,000 in 2016. While there is no ceiling for admission of asylees, the Trump administration worked to narrow the grounds on which asylum seekers could apply and, like the Obama administration before it, used prosecution of asylum seekers as a deterrent for future migration. In January of 2019, the administration issued new Migrant Protection Protocols, commonly referred to as the “Remain in Mexico” policy, by which asylum seekers other than Mexican nationals who entered the U.S. through Mexico were returned to Mexico to await the results of their cases, often in crowded and dangerous tent cities along the border. Further, in 2017 and 2018, the administration unilaterally ended Temporary Protected Status (TPS), which allows individuals from TPS designated countries to remain in the U.S. if humanitarian crises make it unsafe for them to return, such as migrants from El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua, and Sudan (the legality of this order is still being debated in court).

Citing Congress’s unwillingness to fund Trump’s border wall, in April 2018 then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced a “zero-tolerance policy” for those attempting to cross into the U.S. illegally, including asylum seekers. The policy directed U.S. attorneys along the U.S.-Mexico border to prosecute to the extent possible all those apprehended while attempting to enter the U.S. illegally, with Sessions setting an eventual goal of a 100% prosecution rate. The Trump administration was not the first to issue a zero-tolerance policy—the Bush administration in 2005 began implementation of Operation Streamline in certain immigration enforcement zones along the U.S.-Mexico border. According to a 2012 No More Deaths fact sheet, Operation Streamline took away from U.S. attorneys’ prosecutorial discretion to initiate civil deportation proceedings for undocumented immigrants without criminal records, requiring them instead to criminally prosecute all undocumented immigrants for “Illegal Entry” or “Illegal Re-entry” for those previously deported. By 2008, prosecutions for illegal entry or re-entry more than doubled over 2005 levels, from under 40,000 to approximately 80,000. Prosecutions fluctuated under Obama, peaking at over 95,000 in 2013 and then dropping off each year thereafter to a low of around 70,000. The Trump administration’s policy was thus largely a continuation of existing policy, though taken to a further extreme by directing asylum officers to count illegal entry against those applying for asylum.

The Trump administration also deviated from previous administrations by prosecuting parents entering the U.S. with their children, leading to the most notorious outcome of the zero-tolerance policy: family separations. When news of family separations broke in June of 2018, the administration claimed that family separations were not intentionally a matter of policy but rather a consequence of prosecuting adults under the zero-tolerance policy. As suggested in the 2018 Human Rights Watch report, “Q&A: Trump Administration’s ‘Zero-Tolerance’ Immigration Policy” suggests, the administration took the position that since prosecutions of parents required criminal detention and children cannot be held in detention indefinitely, it was therefore necessary to remove children from their parents’ custody. However, Reuters had previously reported in March of 2017 that the administration was considering separating migrant families specifically to deter future migrants. Additionally, the Trump administration had already quietly started to separate families as early as July 2017 through a pilot run of its zero-tolerance policy, further demonstrating that family separations were used intentionally as a strategy of deterrence.

A 2017 internal DHS document titled “Policy Options to Respond to Border Surge of Illegal Immigration” states this plainly. One option, according to the memo, is to “significantly increase the prosecution of family unit parents when they are encountered at the border” and placing their children in the care of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as “unaccompanied alien children (UACs)” (p. 1). It continues, “because of the large number of violators, not all parents could be criminally prosecuted. However, the increase in prosecutions would be reported by the media and it would have a deterrent effect” (p. 1). The document further suggests that ICE and HHS “conduct background checks on sponsors of UACs and subsequently place them into removal proceedings as appropriate” to deter potential sponsors from coming forward (p. 2). This suggestion is made with the clear knowledge that it would result in children being kept in HHS custody for longer periods: “there would be a short term [sic] impact on HHS where sponsors may not take custody of their children in HHS facilities, requiring HHS to keep the UACs in custody longer” (p. 2). The short-term impact on HHS—the document makes no mention of the psychological impact on the children in HHS custody—is justified because, “once the deterrent impact is seen on smuggling and those complicit in that process, in the long term there would likely be less children in HHS custody” (p. 2).

Though poor record keeping between agencies has made it difficult to ascertain the exact number of children separated from parents or other family members, in June of 2021, the Biden administration’s Family Reunification Task Force reported that 3,913 children had been separated from their parents from July 2017 to the end of the Trump administration under the zero-tolerance policy, with another 1,723 cases under review. The Trump administration planned and carried out this policy knowing that migrant children would be psychologically traumatized when separated from their parents. In February of 2019, Jonathan White, then Deputy Director of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), in a Congressional hearing on family separation reported that in a February 2017 meeting at the office of the Commissioner of CBP, also attended by representatives of DHS, DOJ, and ICE, the topic was broached of referring children of apprehended migrant families to ORR custody as unaccompanied children. Echoing the conclusions of the DHS Advisory Committee on Family Residential Centers under Obama, White and his ORR colleagues then raised concerns to DHS of the potential impact on children separated from their families.

Conclusion

As a presidential candidate, Biden promised to undo the damage by the Trump administration and to restore America’s values. This framing, however, ignores that much of the havoc wreaked by the Trump administration relied upon mechanisms put in place by his predecessors. Biden’s platform begins, for instance, with the statement, “it is a moral failing and a national shame when … children are locked away in overcrowded detention centers and the government seeks to keep them there indefinitely” (“The Biden Plan,” para. 1). Yet, the detention centers in which children were locked away under Trump were built under the Obama administration as temporary facilities to address an influx of unaccompanied Central American children. Further, Biden’s condemnation of indefinite detention of minors under Trump obscures the Obama administration’s own attempts to circumvent the Flores Agreement, a 1997 federal court settlement that established a 20-day cap on detention of migrant children. While the Trump administration took the more extreme approach of attempting to terminate the Flores agreement in order to detain minors indefinitely, DHS under Obama interpreted the agreement narrowly to apply only to unaccompanied children, not those who arrived with their parents, in order to keep families in detention indefinitely.

Upon taking office, Biden immediately issued a series of executive orders to halt or reverse certain policies put in place by the Trump administration, including Trump’s “Muslim Ban,” border wall construction (though construction still continues along some stretches of the Texas-Mexico border), and the “Remain in Mexico” policy. The rescission of Trump’s “Remain in Mexico” policy, however, was mostly a symbolic gesture as the Biden administration continued the Trump administration’s use of Title 42 of the United States Code to rapidly expel asylum seekers crossing into the U.S. without authorization. Section 265 of Title 42 allows the U.S. Surgeon General to prohibit entry from countries in which the existence of communicable diseases threatens the public health should a disease be introduced into the U.S. In March of 2020, the Trump administration used the emerging COVID-19 pandemic as justification to invoke Title 42, even though COVID-19 was already present in the U.S. by that time. Because asylum seekers were being expelled under Title 42, rather than deported, they were stripped of their right to appear before an immigration judge. In October 2020, monthly Title 42 expulsions under Trump peaked at 65,783. In February of 2021, Biden’s first full month in office, monthly expulsions reached 72,413, and by May reached 112,958.

In mid-September of 2021, thousands of asylum seekers, mostly Haitians, crossed into the U.S. at a low point in the Rio Grande near Del Rio, TX. CBP, unable to process in a timely manner the volume of asylum seekers, instead held them in a temporary “staging area” under the Del Rio International Bridge, with no running water and a small number of portable toilets. On September 19 under Title 42, CBP began sending asylum seekers to Haiti by plane, with multiple flights scheduled per day. Then, on September 20, images captured by reporters on the U.S.-Mexico border in Del Rio showed Border Patrol agents on horseback using their reins as whips to block asylum seekers who had crossed back into to Mexico to find food from reentering the U.S. These images, which for many recalled images of mounted slave patrols corralling enslaved Africans, sent new shockwaves through the nation. Biden called the actions of CBP “horrible” and “outrageous” and promised an investigation and consequences for those involved. On September 23, the administration announced that CBP agents in Del Rio would no longer use horses in their enforcement operations, but Biden has not, to date, ceased use of Title 42 to expel asylum seekers.

As this article demonstrates, merely reversing Trump era policies—a promise Biden has yet to fulfill, as his continued use of Title 42 demonstrates—will not bring about a humane immigration system. The flaws in our immigration system did not originate under Trump and cannot be solved by reverting to the policies of previous administrations. The time is long past for a complete overhaul of our system, and it is necessary that Democrats take advantage of this moment in which they control the White House and both houses of Congress to pass comprehensive immigration reform. This will likely require Democrats to end the Senate filibuster, which itself will require an amount of political will that the party has so far been unwilling to show. Further, the Biden administration’s chaotic handling of the U.S. military’s withdrawal from Afghanistan and the refugee crisis it created highlight the necessity of recognizing the U.S.’s role in creating the conditions that compel migrants to seek refuge in the U.S. and enacting immigration reform that honors the dignity and humanity of these migrants.

References

Barrick, L. (2016). “Divided by detention: Asylum-seeking families’ experiences of separation.” American Immigration Council. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/divided-by-detention-asylum-seeking-families-experience-of-separation

Chishti, M., Pierce, S., and Bolter, J. (2017). “The Obama record on deportations: Deporter in Chief or not?” Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/obama-record-deportations-deporter-chief-or-not

Haddal, C.C., Kim, Y., and Garcia, M.J. (2009). “Border security: Barriers along the U.S. international border.” Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/RL33659.pdf

“Policy options to respond to border surge of illegal immigration.” https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/5688664-Merkleydocs2.html#document/p2

“The Biden plan for securing our values as a nation of immigrants.” https://joebiden.com/immigration/

Trump, D. (2015, June 16). Presidential campaign announcement [Speech video recording]. https://time.com/3923128/donald-trump-announcement-speech/

The White House (2017)."Executive order 13767 of January 25, 2017: Border security and immigration enforcement improvements." https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/01/30/2017-02095/border-security-and-immigration-enforcement-improvements