The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas

In The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas, Monica Muñoz Martinez provides an excellent account of the long legacies of violence on the Texas-Mexico border, where all Tejanos and Mexican Americans were seen derogatorily as “Mexicans.” She focuses on the communities left in the wake of violence that occurred nearly 100 years ago. She highlights “the stories of those murdered through extralegal executions, … the aftermath of violence, … the parts of life rarely recorded in mainstream histories of border corridos. [She] … reveals the families, neighbors, and communities connected to and shaped by the violence[,] communities that, in turn, had to figure out how to respond to injustice” (pp. 24-25).

In The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas, Monica Muñoz Martinez provides an excellent account of the long legacies of violence on the Texas-Mexico border, where all Tejanos and Mexican Americans were seen derogatorily as “Mexicans.” She focuses on the communities left in the wake of violence that occurred nearly 100 years ago. She highlights “the stories of those murdered through extralegal executions, … the aftermath of violence, … the parts of life rarely recorded in mainstream histories of border corridos. [She] … reveals the families, neighbors, and communities connected to and shaped by the violence[,] communities that, in turn, had to figure out how to respond to injustice” (pp. 24-25).

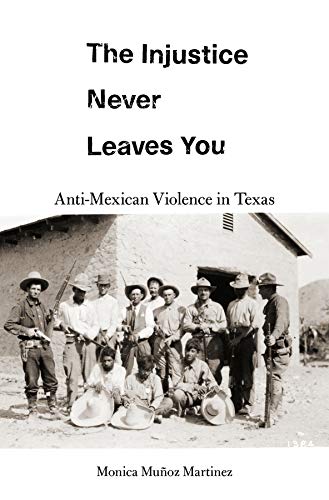

Martinez reconstructs the history of three separate heinous lynching cases using diplomatic and journalistic archives in Mexico and the United States, memories and memorialization of lynchings preserved by the descendants of the victims, photographs of victims, correspondence with Mexican and U.S. diplomats by widows demanding reparations, eye-witness testimonies recorded for posterity, poems, prose, and films full of state violence details, and horrific celebratory postcards of lynchings produced at the scene. She interviewed relatives of victims, recorded oral histories, and listened to their life histories and the tragedies their relatives experienced, including the history of state violence from memory and from their own research.

Martinez challenges mainstream accounts that tend to dehumanize, criminalize, or erase the dead. Instead, she focuses on the history of marginalized and victimized groups—the history of the families that experienced dispossession and loss and thus pass their narratives of injustice from one generation to the next. For relatives of victims, the sentiment of loss, a deep sense of grief, and unanswered questions have remained.

In the first chapter, Martinez reconstructs the history of the lynching of Antonio Rodriguez—a Mexican immigrant suspected of murdering a white woman named Effie Greer Henderson in Rocksprings in 1910. Rodriguez was arrested and the local sheriff put him in Edwards county jail. Later that afternoon while he was jailed, a mob grabbed him from his prison cell and burned him alive.

In the second chapter, Martinez examines extrajudicial killings of several Mexican ranchers by a Ranger company in 1915—a period of racial violence accompanying the period of the Mexican Revolution. Jesus Bazán and Antonio Longoria were shot in the back by a Texas Ranger, Captain Ransom, and two citizens, William Sterling and Paul West. The victims fell from their horses and died on the side of the road. They were denied immediate proper burial. Later two of Longoria’s friends took the risk and buried their remains with the help of other witnesses. These killers were never prosecuted.

In the third chapter, Martinez describes what is known as the “Porvenir Massacre” of January 1918 in which a company of Texas Rangers executed fifteen Mexican and Tejano men and boys ranging from sixteen to sixty-four years of age. The victims resided in Porvenir, a rural ranching community in the Big Bend region. Survivors of that massacre were women, including two pregnant women, children, and elderly men. The Porvenir massacre became the target of a series of inquiry by Mexican American attorneys into the conduct of the Texas Rangers, but these legal inquiries against the government did little to help victims of the massacre. The descendants of the massacre still wait for accountability, punishment, and acknowledgement of the heavy memories of violence their families endured and carry with them.

In the fourth chapter, Martinez situates anti-Mexican and Tejano violence within a larger culture of racial violence and examines efforts in 1919 by Jose T. Canales, a state representative, to reform the Rangers and investigate police abuse and rights violations of residents in the border region. Martinez links “the culture of impunity that allowed anti-Mexican violence to thrive in Texas … to the ongoing history of anti-black violence in the state. Both these histories emerge from ideologies of white supremacy in the American South and West … and helped state authorities justify extralegal violence” (p. 174). Martinez points out that “in Texas, there is no shortage of public celebrations that honor icons of state violence. For too many, it is racism memorialized and celebrated in plain sight” (p. 226).

In the fifth and sixth chapters, Martinez critically examines the myth of the Texas Rangers as great heroes as constructed in the works of historians and residents, museum exhibits, state monuments, and classroom textbooks. In Texas, myths fused ideological beliefs of freedom and democracy with a simplistic racial narrative that Anglos are superior to racial and ethnic minorities. According to Martinez, “Anglo settlers are honored as pioneers who guaranteed Texas modernity by rescuing the region from threatening Indigenous nations and corrupt Mexicans” (p. 230). Such myths erase the true history of Texas; that of injustice.

The Injustice Never Leaves You offers three important lessons for readers: 1) the role of the state in anti-Mexican violence and the failure to confront violent policing practices in the 1910s; 2) the roles and constructed myths of Texas Rangers in unleashing violence against Mexicans; and 3) the historical narratives and memories from survivors affected by the trauma across the generations. Innocent Mexicans, Tejanos, and Mexican Americans were brutally murdered by being lynched, burned alive, shot in the back, or executed. Texas Rangers, local enforcement officials, and local ranchers participated in those heinous killings but were rarely prosecuted.

Martinez provides a compelling case for holding state institutions accountable for implicitly participating in such violence, for portraying Texas Rangers as pioneer heroes instead of villains who committed numerous murders, and for covering up the history of violence against Mexicans. As in other cases of state violence, genocide, and crimes against humanity, it is crucial to remember those who were killed, making sure that the memory of racial violence is not forgotten, and that survivors of that violence are supported. Martinez puts it best when she writes: “Remembering the past is also about knowing the present” (p. 296). State violence and police brutality along the Texas-Mexico border and across the country are ongoing still today. Martinez ends the book by stating: “The more people understand the long consequences of violence, the more likely we will be able to intervene against—to denounce outright—the violence and death that continue today” (p. 300).